History and Background

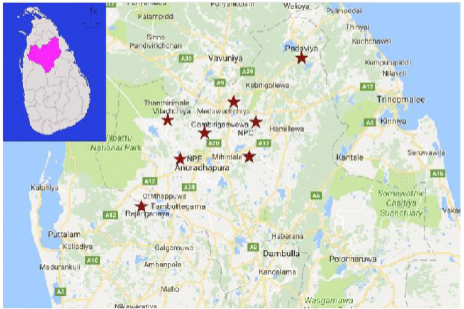

This project is based in the Lower Kanadara Oya sub-river basin of the Malwathu Oya Basin in the Anuradhapura district of Sri Lanka. This sub-river basin and its component geospatial features that are of great relevance to investigating connections between land use, socioeconomic conditions, water quality of major sources used by humans and biodiversity. This project will gather and analyse field and past available data from this sub-river basin including the flowing waters of the Lower Kanadara a Oya as well as from a few of its tank cascade systems.

Below is a very brief historical, cultural and environmental outline of where the field sampling will be carried out. Those who visit this area will not come away disappointed!

Ancient civilization of Anuradhapura

Anuradhapura is the first capital of Sri Lanka located in the north-central province of Sri Lanka (https://www.ceylonexpeditions.com). It was the greatest monastic city of the ancient world and was ruled from the 4th century BC to the 11th century AD by more than 100 Sri Lankan kings (https://www.reddottours.com).

According to the earliest chronicles, Sri Lanka was inhabited by migrants from India, namely princes Vijaya and his team from Lata country. They established settlements adjacent to several river valleys in the dry zone of Sri Lanka. The settlement called Anuradhagrama closer to the present-day Malwathu oya which was established by the minister called Anuradha gradually became the centre of the civilization. (Geiger, 1908; Oldenberg, 1879).

According to the literature, by the 4th century BCE, the Anuradhapura settlement formed a city by King Pandukabaya.

The next important step in the development of the Anuradhapura landscape was the introduction of Buddhism in the 3rd Century BCE in the reign of King Devanampiyathissa (Geiger, 1908).

Sri Lankan history is full of achievements of ancient kings who contributed to the development of water resources. Construction and upkeep of these irrigation systems became massive undertakings and an indigenous expertise to do so developed over the centuries, which appears to have been called upon by other countries of South Asia (Dharmasena, 2011).

Not only that, the Cultural Triangle of Sri Lanka which is a major tourist attraction, is found on Sri Lanka’s central plains and encompasses the cities of Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa, Sigiriya and Dambulla. Anuradhapura was the centre of Theravada Buddhism for many centuries. UNESCO named it as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1982 under the name of Sacred City of Anuradhapura (https://whc.unesco.org/). This ancient hydraulic civilization of the dry zone disappeared after the twelfth century AD. Climatic change, malaria, depletion of soil fertility, foreign invasions, and famine are some of the reasons cited (Dharmasena, 2011). But the marvels of this civilization can still be seen in what is left today.

Visitors can enjoy stunning views of this bygone civilization combined with Sri Lanka’s rich biodiversity. This area is replete with villages dating back centuries, ruins of ancient monasteries and medical treatment centres and forest landscapes that showcase the biodiversity of the dry zone of Sri Lanka. The southwestern quarter of this island combined with the Western Ghats of India is one of the 36 global biodiversity hotspots of the world.

Malwathu oya

Malwathu Oya (called Aruvi Aru at the lower reaches) has a total length of 162 km and is the second longest river basin in Sri Lanka. It originates at Ritigala and Inamaluwa Hills (766 m and 383 m above MSL respectively) in the North Central Province and flows to the sea at Arrippu in Mannar district. About 70% of the upper catchment of Malwathu Oya is located in the Anuradhapura District while the lower catchment is located in Vavuniya and Mannar Districts (https://www.irrigation.gov.lk).

The Kanadara Oya is the main tributary of Malwathu Oya which by creation of a large reservoir; “Mahakanadarawa Wewa” (human-made reservoirs also known as tanks) was built during the era of the Anuradhapura kingdom (4 C BC to 11 C AD) (https://www.ft.lk). The main focus of this research is on the Lower Kanadara Oya River basin. There is a great deal of history behind the more than 3000-year-old tank system of Sri Lanka which was built by the ancient rulers, mostly in the dry zone to overcome water scarcities in that region. There are nearly 10245 tanks and reservoirs (Costa, 1994) still existing today and they are one of the best adaptation strategies for modern-day climate change.

Tank Cascade Systems of Sri Lanka

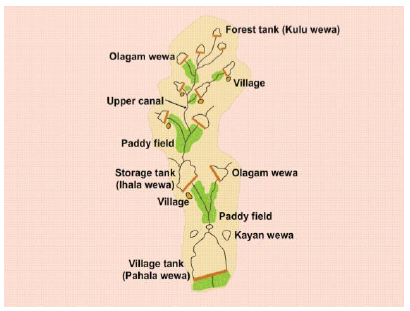

Work by Panabokke et al. (2002) indicates that village tanks are not situated randomly, but organized to collect rainwater from well-defined micro catchments. These individual tanks are components of large systems or units called ‘cascades’, defined as a connected series of village irrigation tanks organized within a micro— (or meso-) catchment of the Dry Zone landscape, storing, conveying, and utilizing water from an ephemeral rivulet’ (Madduma Bandara, 1985). The main sampling unit of this research is the tank cascade system of the Lower Kanadara Oya sub-river basin.

Irrigation tanks are often not isolated tanks but are part of a larger interconnected system of tanks called a ‘tank cascade system’. It is connected by a series of tanks organized within a micro-catchment. A ‘cascade system’ is the traditional unit used in the management of tanks. From ancient times it is referred to as ‘Ellangawa’. The term is made up of the Sinhalese words ‘ellan’, meaning hanging and ‘gawa’, meaning one after the other. The image below shows the organization of tanks and their connectivity within a typical tank cascade system. The image below shows the micro-catchment of a typical village tank, which is usually the main tank of a cascade system.

The village tank is the main component of the tank cascade system. Water from all other tanks in the system drains into the village tank. This tank is used for agriculture, as well as other community activities. A typical village comprised of the village tank and a field below it.

Although the main purpose of the tank cascade system was to provide water for irrigation purposes, the tank cascade system included tanks that had other purposes too. The purposes of the other tank types are connected in different ways to provide a good and constant supply of water to the village tank. The proper functioning of the village tank is therefore dependent on the condition of all the other types of tanks that are found in the tank cascade system. The ecosystem services and support to biodiversity varies considerably between each type of tank (Dharmasena, 2010; Someratne et al., 2005). There are several types of small tanks within a cascade system serving different purposes including ones for providing water for wild animals, these forest tanks reduce the likelihood of these animals coming into the village to look for water and damaging crops.; ones to trap sediment to avoid siltation and sedimentation of the main village tank and to control salinity.

References

- Abeywardana, N., Bebermeier, W., & Schütt, B. (2017). The hinterland of ancient Anuradhapura: Remarks about an ancient cultural landscape. Journal of World Heritage Studies, 2017, 40-47. https://www.academia.edu/download/80111590/index.pdf

- Dharmasena, P. B. (2010, December). Essential components of traditional village tank systems. In Proceedings of the National Conference on Cascade Irrigation Systems for Rural Sustainability. Sri Lanka: Central Environmental Authority. https://www.academia.edu/download/34340543/Essential_Components_full_paper.pdf

- Dharmasena, P. B. (2011). Evolution of hydraulic societies in the ancient Anuradhapura Kingdom of Sri Lanka. Landscapes and Societies: Selected Cases, 341-352. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-90-481-9413-1_21

- Geiger, W. 1908. Mahavamsa: Great Chronicle of Ceylon. H. Frowde.

- http://iucnsrilanka.org/Kapiriggama/cascade-2/what-is-a-cascade/

- https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/200/

- https://www.ceylonexpeditions.com/anuradhapura-sacred-city-sri-lanka

- https://www.ft.lk/columns/Lower-Malwathu-Oya-project-%E2%80%93-A-series-of-misconception-errors/4-639380

- https://www.irrigation.gov.lk/web/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=83&Itemid=193&lang=en#:~:text=Malwathu%20Oya%20(called%20Aruvi%20Aru,at%20Arrippu%

- https://www.reddottours.com/sri-lanka/cultural-triangle#:~:text=The%20Cultural%20Triangle%20is%20found,based%20on%20agriculture%20and%20Buddhism.

- Madduma Bandara, C. M. (1985). Catchment ecosystems and village tank cascades in the dry zone of Sri Lanka. In U. L. Lungquist, & M. Halknmark (Eds.), Strategies for river basin development. Riedel Publishing Co

- Murray, F. J., & Little, D. C. (2000). The nature of small-scale farmer managed irrigation systems in North West Province, Sri Lanka and potential for aquaculture. Working Paper SL1.3. Project R7064.

- Oldenberg, H. 1879. Dipavamsa. Asian Educational Services.

- Panabokke, C. R., Sakthivadivel, R., & Weerasinghe, A. (2002). Small tanks in Sri Lanka: Evolution, present status and issues. International Water Management Institute (IWMI).

- Panabokke, C. R., Tennakoon, M. U. A., & Ariyabandu, R. De. S. (2001). Small tank system in Sri Lanka: Summary of issues and considerations. In H. P. M. Gunasena (Eds.), Food security and small tank systems in Sri Lanka: Workshop proceedings. National Science Foundation

- Silva, R. 2000. Development of Ancient Cities in Sri Lanka with special reference to Anuradhapura. Reflections on a Heritage: Historical Scholarship on Pre-modern Sri Lanka: p.49–81.

- Somaratne, P. G., Jayakody, P., Molle, F., & Jinapala, K. (2005). Small tank cascade systems in the Walawe River Basin (Vol. 92). IWMI. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=tuUaBQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=somaratne+et+al,+2005&ots=EB_BcTAKLY&sig=DDDm5eRXDngSxICiFWJQgUi27C0

- Wagalawatta, T., Bebermeier, W., Hoelzmann, P., Knitter, D., Kohlmeyer, K., Pitawala, A., & Schütt, B. (2017). Spatial distribution and functional relationship of local bedrock and stone constructions in the cultural landscape of ancient Anuradhapura (377 BCE–1017 CE), Sri Lanka. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 13, 382-394. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352409X17302596

- Costa, H. H. (1994). The status of limnology in Sri Lanka. SIL Communications, 1953-1996, 24(1), 73–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/05384680.1994.11904027

- PHOTOGRAPH CREDITS DUE TO THARANGA WIJEWICKRAMA